Introduction

2024 is more than just an election year. Perhaps this is the election year.

Globally, more voters than ever before will go to the polls, as at least 64 countries (plus the European Union)—representing approximately 49% of the world’s population—are scheduled to hold national elections, the results of which, for many, will have long-term consequences.

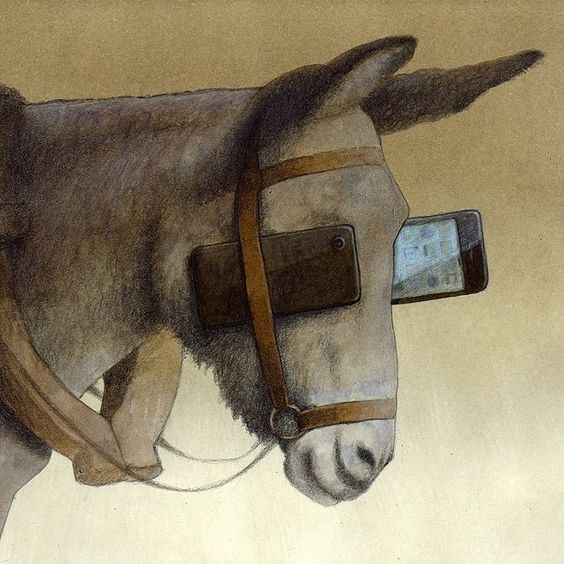

In an era where truth seems malleable and reality is often a point of contention, the term ‘gaslighting’ has found its way into the modern lexicon, especially within the realm of politics. Originally coined from the classic stage play and film that depicted a husband’s psychological manipulation of his wife, gaslighting has evolved to describe a form of deception that sows seeds of doubt, making individuals question their perception, memory, or sanity. In the political arena, this tactic takes on a grand scale, impacting not just individuals but entire societies. It is a strategy that destabilises and disorients, leaving public opinion adrift in a sea of manufactured uncertainty.

Historical Roots of Gaslighting

The term “gaslighting” traces its origins to the dramatic arts, first appearing in the British play “Gas Light” from the 1930s. The narrative centres on a husband who, in an attempt to steal his wife’s fortune, manipulates her into questioning her reality and mental state by dimming the gas-powered lights in their home. When she notices the change, he denies it, causing her to distrust her perceptions and memory. This play was later transformed into George Cukor’s 1944 classic film “Gaslight.” (7.8 on IMDB). The film, starring the gorgeous Ingrid Bergman and the attractive Charles Boyer, was nominated for seven Oscars, winning six, including Best Actress. It introduces the world to an insidious type of psychological manipulation in which the victim is taught to question their sanity, usually by someone close to them.

The methodical and deceptive techniques showcased in the story provided a vivid script for understanding how manipulation works, eventually permeating into psychological literature as a term to describe similar tactics in real-life scenarios. Over time, the use of gaslighting has extended beyond individual relationships to encompass broader applications, including political spheres where truth and trust are essential commodities.

Gaslighting in Today’s World

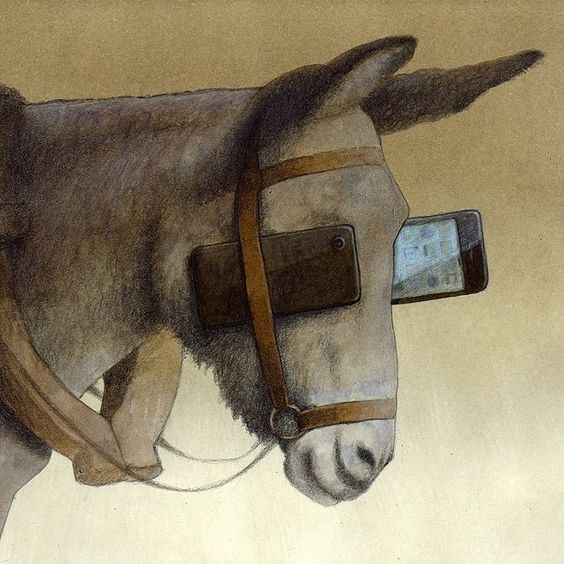

Gaslighting in today’s world has transcended its dramatic origins to become a prevalent form of psychological manipulation in various spheres of life. This insidious tactic causes individuals to doubt the legitimacy of their memories, perceptions, and sanity, often leading to a sense of profound disorientation and psychological distress. Its presence is not confined to personal relationships but extends into the professional realm, where bosses, family members, and other figures of authority use it to maintain control or assert dominance.

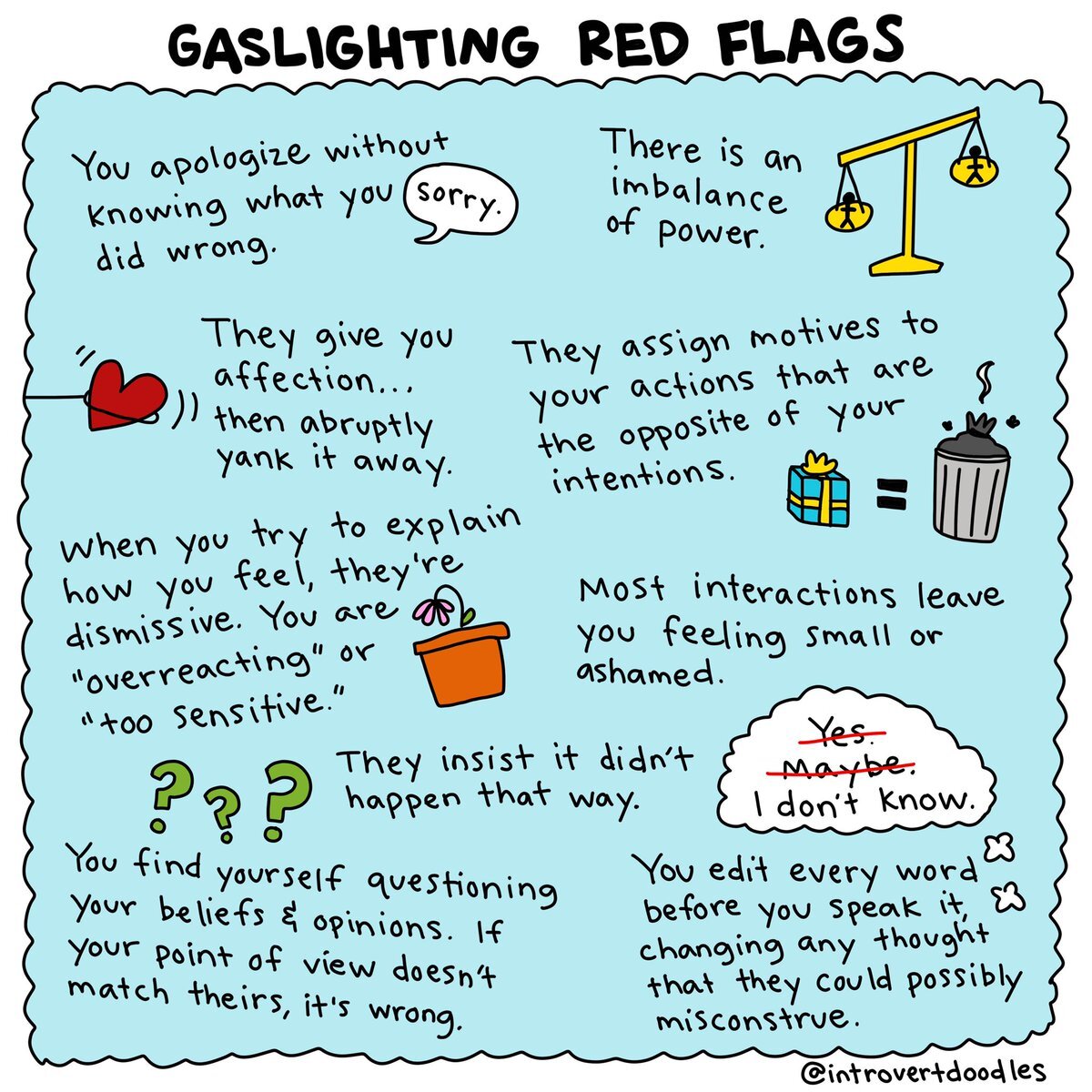

The phenomenon has also become a significant talking point in understanding emotional manipulation and abuse, as it disrupts an individual’s belief in their own experiences and can diminish their self-esteem. Recognising gaslighting is the first step in countering its effects, with strategies including taking space from the situation and collecting evidence to reaffirm one’s reality. Awareness and education on this topic are essential to empower those affected to respond effectively and reclaim their autonomy over their thoughts and feelings.

The Impact of Gaslighting on Individuals and Society

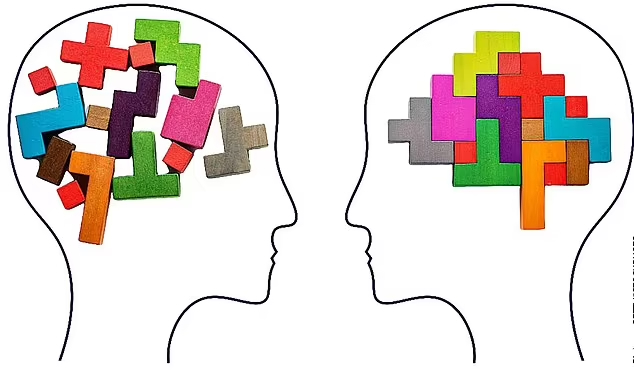

The impact of gaslighting on individuals can be deeply corrosive, with long-term psychological effects. Victims often grapple with anxiety, depression, and a pervasive sense of confusion as their ability to trust their own thoughts and emotions is systematically undermined.

Over time, the persistent doubt sown by gaslighting can lead to a diminished sense of self-worth and a profound identity crisis.

At a societal level, gaslighting can undermine the fabric of trust that holds communities together.When used as a tactic in discussions about politics or media, it has the potential to erode public trust in institutions and facts, contributing to a post-truth society in which altered narratives obfuscate objective reality.This erosion of common agreement on fundamental truths can be harmful to democratic processes and civic involvement because it calls into question the very foundation upon which informed judgements and social consensus are founded.

To combat these adverse effects, it is crucial to foster environments where open dialogue is encouraged, and individuals can seek validation and support. Education on the signs of gaslighting and promoting critical thinking skills are key measures in empowering people to resist manipulative tactics and restore trust in their perceptions and in the shared reality of society.

Recognising Gaslighting

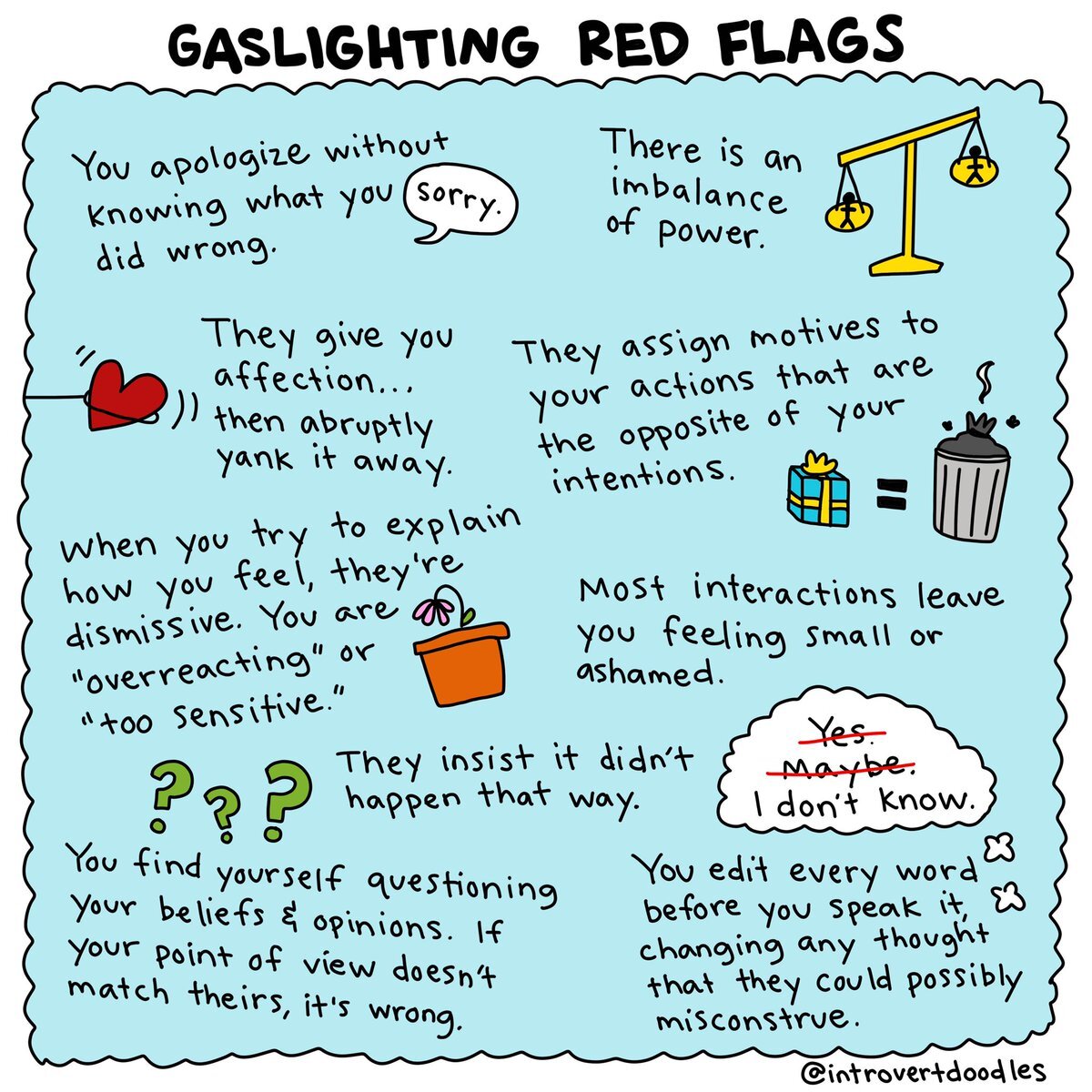

Recognising gaslightin g is the first critical step in countering its harmful effects.

g is the first critical step in countering its harmful effects.

The process begins by identifying the technique as what it is – a deliberate form of emotional manipulation. Be vigilant for common phrases that may signal gaslighting, such as dismissals of your feelings or accusations that you’re overreacting. It’s important to document interactions that feel manipulative, as keeping a record can help you discern patterns and confront the gaslighting with evidence.

Lean on your support network for a reality check. Friends, family, or a therapist can provide an outside perspective that counters the gaslighter’s narrative. Establishing strong boundaries is also key; decide what behaviour you will not tolerate and stick to it. If a conversation becomes a “crazy-making game,” it’s crucial to calmly state the facts and, if necessary, disengage to maintain your mental health.

Educating yourself and others about the signs of gaslighting can empower you to resist these tactics. Awareness is a powerful tool that not only helps victims but also creates a culture where gaslighting is less likely to thrive.

Mitigating the Effects of Gaslighting

Mitigating the effects of gaslighting involves a multifaceted approach that starts with recognising and acknowledging the abuse. Once identified, it’s essential to reaffirm your reality and trust in your perceptions. Establishing a support system is crucial, as trusted friends, family members, or professionals can provide validation and counteract the gaslighter’s narrative.

Mindfulness and stress-reduction techniques can be incredibly effective in alleviating the anxiety and PTSD symptoms that often result from prolonged gaslighting. Regular practice can lead to a calmer, more invigorated mental state, helping to restore balance and inner peace.

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) offers tools to recognise manipulation and build psychological resilience. By challenging the distorted thoughts and beliefs instilled by the gaslighter, you can begin to regain confidence in your judgement and decisions.

Remember, healing from gaslighting is a process, and being kind to yourself is vital. Allow yourself to experience and validate your emotions without judgement as you work towards recovery.

g is the first critical step in countering its harmful effects.

g is the first critical step in countering its harmful effects.

One Response to Gaslighting – Not what I Thought 💭